Opening Friday 26 September 6pm

Exhibition continues 1 November

Artist / Curator conversation Saturday 1 November 3pm

New work by Christian Lock

Catalogue of works

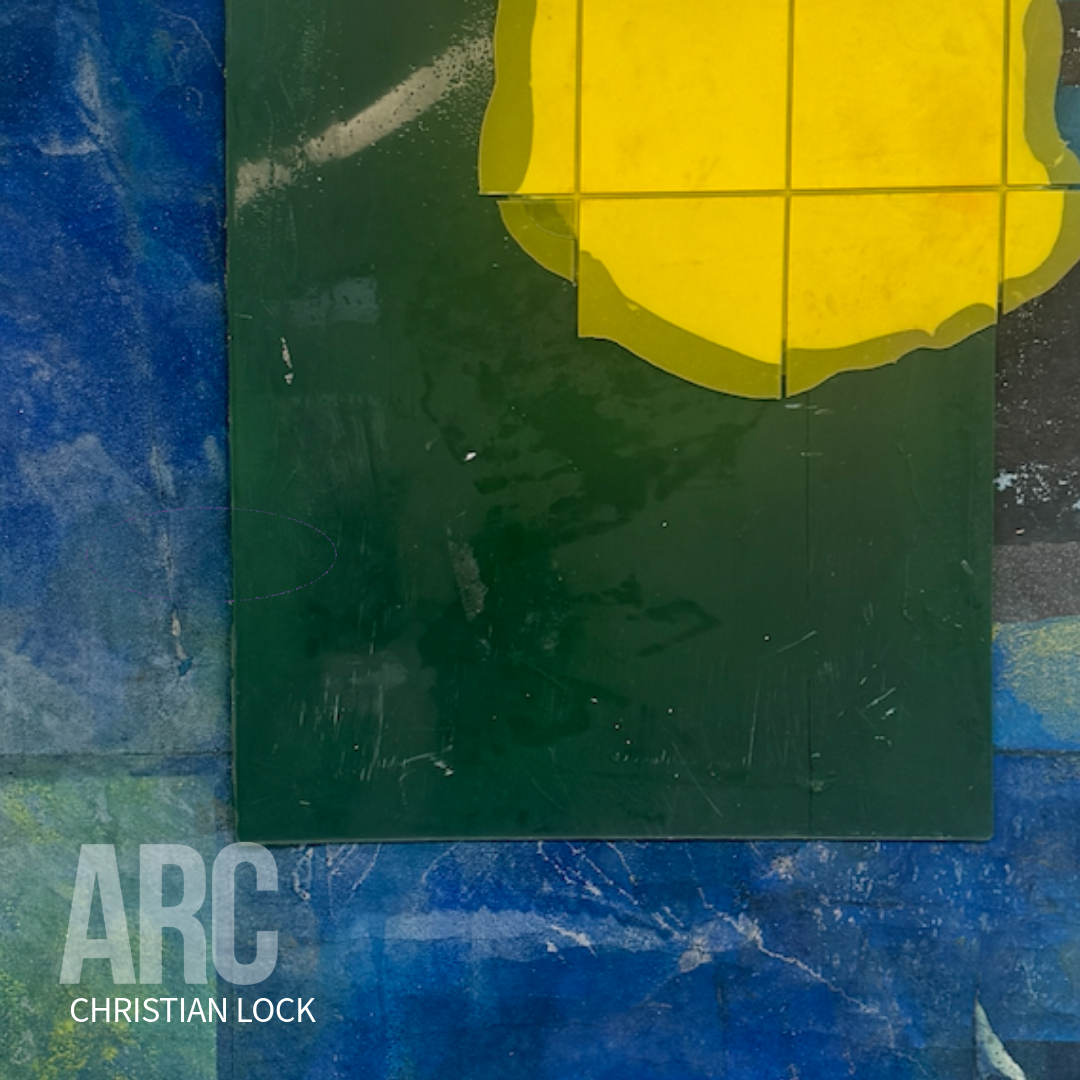

Arc / Christian Lock – Michael, 2025

The exhibition Arc comprises four large paintings by Christian Lock. Together they chart key points in a larger group of works that has occupied the artist from 2022–2025. Works from this group have been exhibited widely, and the second part of this essay reproduces an essay written to accompany earlier showings from this group in Adelaide and Los Angeles in 2023. These works are united by their exploration of the techniques, materiality and effects afforded by spray paint. These four paintings here present the full arc of this series, including the complex work that began it, Again (2022–2025), and to which Lock has returned to in the years since then. Point in Wasting (2023) is from Lock’s series Techgnostic Transmissions (TT), which makes up the larger part of this group of works. In TT, the dematerialising and ambiguous spatiality of the spray paint becomes most fully realised, and the intensity of the colour and color contrasts most marked. The other two paintings in Arc, Little Brother and Mountain (both 2023–2025), show a return to new kinds of material experiment.

Again’s title clearly signals the many returns Lock has made to this canvas. It is covered with so many sprayed and stained layers that in places the resultant crust has cracked, buckled and fallen away, becoming something of a beautiful ruin, even as the artists has continued to build it. In the lower centre, where a wedge of paint has fallen away, grey-black underpainting shows through a millimetres-thick accretion of dazzling yellow and blue sprayed paint. In this context this grey black wedge has the colouristic impact of those notes of black Renoir introduced into his paintings against similarly dazzlingly coloured grounds – the velvety black of a bow against a brightly coloured dress, for instance. Black, painters sometimes say, is not merely an absence of light, as physicists have it, but a colour sensation in itself. Another kind of transformation occurs here as one veil of spray covers another. It builds up, visibly, into a crust of pigment. Yet these veils can also seem to let light through, to become somewhat transparent or translucent, suggesting an atmospheric, perhaps cosmic, depth. In later works these transformations from the material to the spatial are attained more readily (and become an occasion for spiritual reflection also). But the effect is never more impressive than here, where the material from which the painting is made seems so implacably obtrusive, that its transformation is made all the more striking and affecting. Again also shows Lock’s initial experiments with staining the canvas to make what would become in the Technostic Transmissions organic biomorphs and pinwheel-like geometric forms that organize the space of the paintings. In those later paintings, they that act less like elements to be balanced within a composition, and more as dispersers or transmitters of energy across the picture plane. Here they also add to the material and aerial qualities of the work, an intermediate state of matter – a sense of water or fluid. Their finger-like forms also suggest, to me at least, the ‘pillars of creation’ captured by the Hubble telescope – dark columns of dust moving through an unfathomably vast nebula. (Fig. 2.)

Other striking elements of Again are the polyurethane and silicone sheets that hang from the top of the canvas. The yellow silicone sheet is amorphously shaped and has a gridded pattern; it lays over the more rigid translucent green polyurethane. These two elements hang off-centre, and about halfway down, occluding that part of the canvas that they overlap. In one respect these elements act as pure painting – they provide a new, contrasting and harmonizing elements of colour. They also use the logic of collage or assemblage to achieve this – there is a sense that these elements are merely provisional, and could be moved, rather than being an integral part of a design. In this way they once more afford an escape the expectations of modernist composition – where elements of a painting must be visually balanced against each other to create a sedate equilibrium in the manner, say, of Mondrian’s Neoplasticist abstraction.

All of these features – spray painting, the sense of atmospheric spatiality, the staining, and the logic of the collage – are reprised in the other paintings shown here. Point in Wasting, as I have mentioned, is part of the series Techgnostic Transmissions. Here the draped latex takes on the character of a sunflower, an orange aureole around a grey-black centre, the orange efflorescing against the ground of intense ultramarine blue. Little Brother and Mountain also began as entries in TT, as their blue, stained and sprayed grounds suggest. Here their original latex overlays are replaced with elements adhered to the canvas surface. In these works the sense of the atmospheric and spatial is countermanded by the blurts of epoxy resin paint and collaged elements which recall Bauhaus experiments with colour, materials and process. In Little Brother this takes the form of three rectangles, of red, yellow and blue. These sit on the canvas surface, pressed into a pool of white epoxy resin, like blocks of watercolour paint sitting unadulterated in a painter’s portable tray. Mountain explores similar effects using pieces of laminated woodgrain, again sunk into white resin, and partially covered with brisk, perfunctory brushstrokes that suggest a happy painter-decorator coming off work for the day. Lock has come from illusions of atmospheric spatiality – and as I discuss below, spirituality – and here returned to a vision that reaffirms materiality, physical process and the smaller, closer-to-hand sensations of colour, texture and form. Where these works earlier suggested cosmic depth, now the suggests a world of sensations at arm’s reach. What should one make of this arc? Perhaps it should be said that the time in the spray booth is not sustainable for an artist – even with the protective gear that Lock wears, it is bound to take a physical toll sooner or later. Perhaps too, at a philosophical level, one cannot live in the realms of the sublime and the numinous permanently. The physical and spiritual, so some philosophers say, are aspects of the same reality, two sides of the same coin, neither of which should be favoured or denied if a full understanding of ourselves and the universe is to be had. In the case of art something like this is certainly true. Whatever effects one can creates in art – whether illusion of space or the sense of the spiritual – they originate in the manipulation of materials. And they are sustained by technique and materials, much as the soul and mind are sustained by the body. So perhaps Lock reminds us of something fundamental about our own condition when he draws our attention back to technique, process and matter.

Indeed, the world of the mundane and familiar is indispensable in other ways too. In the exhibition that accompanies Arc, Gerry Wedd addresses the algal bloom that currently blights our shores, and – many of us worry – portends greater environmental calamities. Lock, too, is alive to these concerns. Like Wedd he is a surfer (this year he placed first in the Over 55 Men’s Division at the Australian Surf Championships) – and he lives close to the beach at Noarlunga. Lock is now looking beyond the trajectory laid out in Arc, and is developing work that addresses this disaster. Fans of his painting can see two powerful new paintings on this topic as part of Good Bank Gallery’s exhibition Toxic Surf, which opens Friday 10 October, 6–9pm.

– Michael Newall, 2025

2.

Lock tells me that the intense blue that he uses in this series [Technostic Transmissions] comes from the blue colour one can see when you press or rub your closed eyes. Such colour effects are called phosphenes. For some, these colours are just the electrical flickering of the visual system as it is prodded and pressed. For Lock, these colours are a symptom of another reality beyond or outside our physical world. Over a century ago, Kandinsky described similar beliefs. When one experiences colours unattached to or independent of physical objects in the world, we see the non-physical, spiritual character of colour. This was most apparent in his synaesthetic experience of colour: intricate arrangements of colours prompted by music but attached to no physical surface. More recently, philosophers have argued for the non-physical character of colour experience. In a famous thought experiment, devised by philosopher Frank Jackson, we are asked to imagine a scientist, named Mary, who knows everything about the physics of colour and its optical and neural processing, but has not herself experienced colour because for her entire life she has remained in a room painted and furnished only in black and white. (And, we will want to add, she has never pressed her eyes and seen Lock’s coloured phosphenes.) Jackson asks, does Mary experience anything new when she leaves her black and white room for the first time, and sees the world in colour? Jackson says yes – she learns what it is like to see all the colours, the intense blue of the sky, the yellow of the sun, and so on. But Mary already knows every physical fact about colour vision. So, what is it that she has learned? She has learned a non-physical fact – and it follows that what she has learned, what blueness is like as an experience, is non-physical. It is a short jump from there to understanding our experiences of colour as having a meaningfully spiritual character.

Much of Lock’s colour in these works is made with spray paint, sometimes applied over patterned and textured prints. The paint itself is matt, and sprayed on to the surface, it produces a soft quality, like pure pigment. The non-reflective character of the paint ensures that no reflection diminishes the purity of its colour. Lock also tells me that ultramarine blue has a slightly fluorescent character. It absorbs ultraviolet light and transmits some of that energy as blue light. I’ve failed to find anything about this in the scientific literature on pigments, but looking at the intense blues of some of Lock’s paintings here, I find it easy to believe. Lock’s intense blues also remind me of the intense ‘self-luminous’ hues that Paul Churchland calls ‘chimerical colours’, and I wonder if similar effects enhance some of Lock’s intense colours. However these intense effects are produced, they have a quality that seems phosphene-like, somewhat detached from the world of physical objects, emanating from the canvas, encouraging us to acknowledge their existence as pure sensation.

If one continues to press or rub one’s eyes, one may see grid and mosaic-like geometric patterns. These can also be seen in lucid dreaming, or in response to sensory deprivation, strobing lights or psychedelic drugs. The psychologist Heinrich Klüver identified the various forms that these patterns can take. For those who see them, they can suggest glimpses of otherworldly architecture and decoration. The geometric elements in Lock’s works suggest such fragments – pieces of moulded latex patterned with a grid and laid over the canvas, or patterned with a more complex geometry and integrated within the canvas’s powdery surface. All suggest structures that extend – invisibly – further, perhaps indefinitely. For me, they recall the glimpse that the traveller in the Flammarion engraving (fig. 3) gets of a world of neo-Platonic forms as he lifts the curtain surrounding the mundane world of appearances.

Geometry and grids are also features of the modern, technological world. They are present in real physical forms, large and small, in concrete, steel and wiring, and in the invisible but no less physical flows and networks of energy and information. For Lock, the geometries and patterning that appear in his works are especially associated with networks of energy and information. Here, Lock’s ideas show an affinity with those of Erik Davis, whose 1998 book, TechGnosis: Myth, Magic and Mysticism in the Age of Information, drew attention to the many parallels underlying thinking around information technology and ancient spiritual ideas. He focused especially on Christian Gnosticism, which put great store in secret knowledge and mystic experience – ideas vividly visualised in the Flammarion engraving. Of course, technology, as ordinarily understood, is a physical phenomenon. But Davis shows that underlying the thinking of many of its most visionary proponents are impulses that have an affinity with strands of early Christianity: a disdain for the body, a fear of death, and a desire for immortality. For Davis’s “techgnostic”, these impulses drive a desire to become one with technology, and to identify the technological with the spiritual.

How far can we follow such ideas? Some say that we are becoming fused with technology already. For philosophers Andy Clark and David Chalmers, our minds may already extend beyond our skulls to the technology that we depend on for cognitive processes such as memory, calculation and visualisation. We often “outsource” these activities to technology: social media sites hold our memories, computers enhance our ability to calculate, and CGI and AI aid our ability to visualize. So, much cognition goes on outside our skulls. Thus, for Clark and Chalmers, our minds – which is also to say our selves – may extend beyond our bodies into technology. We may already be cyborgs of a kind: amalgams of flesh, technology and invisible flows of energy and information. Clark and Chalmers’s thinking does not go quite so far as Davis’s, but their ideas are consistent. As Davis says, “information technology transcends its status as a thing, simply because it allows for the incorporeal encoding and transmission of mind and meaning.”

Lock thinks of his works as ‘techgnostic transmissions’: transmissions of mind and meaning that hint at the kinds of understandings I have sketched here. His works present the viewer with the non-physical character of colour, and suggest a world in which one’s sense of self extends beyond one’s body into abstract, technologised spaces. Look at these works, and something else will be straightaway apparent. They show that these revelations in our understanding of reality, and changes in our sense of self, need not be threatening, but can be affirming, life-enhancing and oceanic in feeling.

– Michael Newall, 2023