Opening Friday 26 September 6pm

Exhibition continues 1 November

Artist / Curator conversation Friday 24th October 6pm

New work by Gerry Wedd

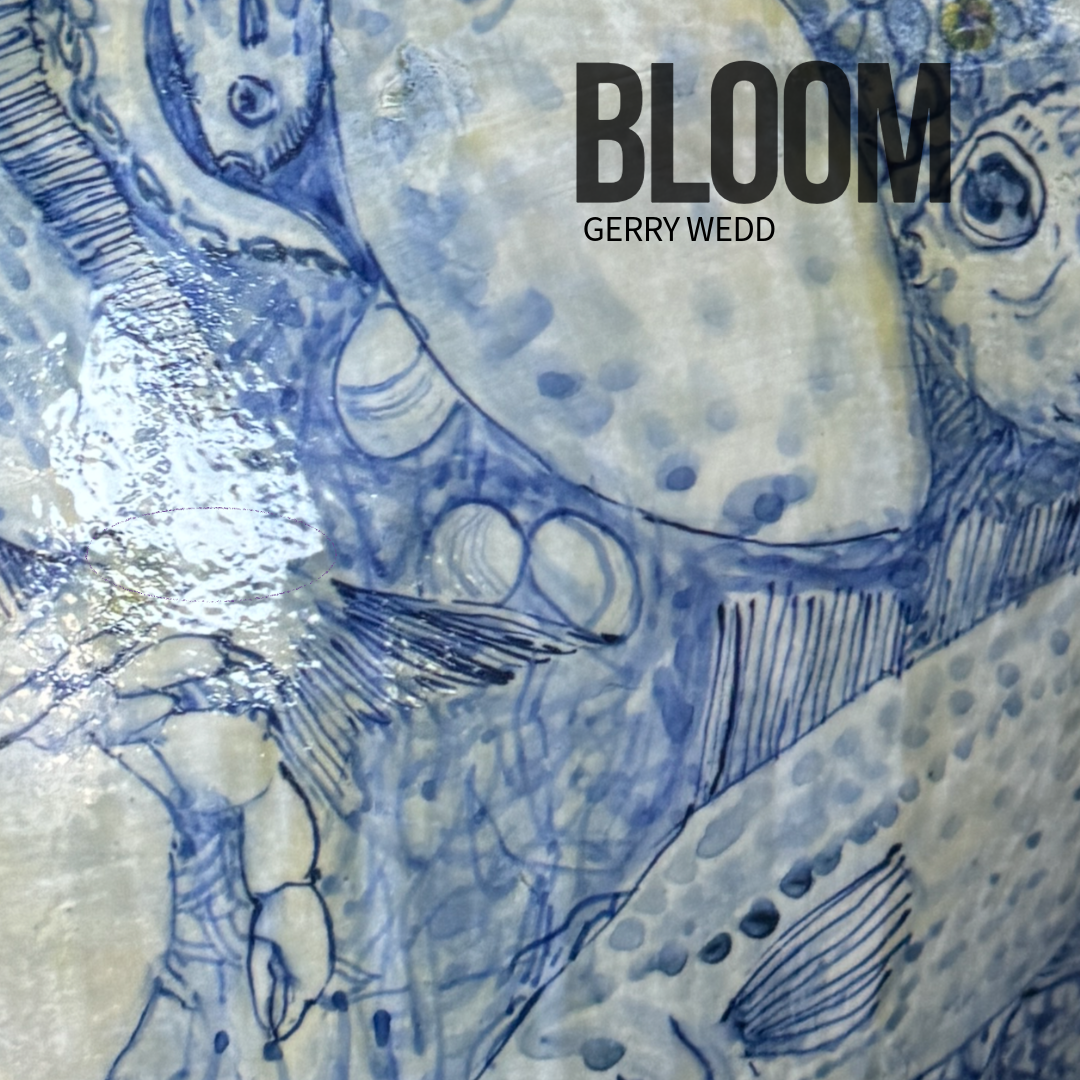

BLOOM presents new ceramics by Gerry Wedd. Plates, cups and pots are adorned with finely painted images of sea creatures washed up dead along South Australia’s coastline, a direct response to the current algal bloom. While confronting in subject matter, the works are underpinned by Wedd’s wry humour and sharp political edge, transforming everyday objects into a commentary on environmental collapse.

Catalogue of works

Bloom / Gerry Wedd – Michael Newall, 2025

Since March this year, Gerry Wedd has noticed the discolouration caused by the algal bloom in the waters of the Southern Ocean off Port Elliot, where he lives. Like many others for whom the coast is a touchstone, he has felt the irritation that the bloom’s dispersion into the air causes in the eyes and throat, and observed the dead animals washed up on the shore, one population of creatures after another. At the time of writing, after originating in the unseasonally warm waters of the Southern Ocean early this year, the bloom is moving up the east coast of Gulf St Vincent, to the suburban beaches of Adelaide, continuing to kill, so it seems, all the sea creatures in its path. We now wait to see what will happen as summer approaches, and the waters warm again.

Wedd’s new body of work, Bloom, is a direct response to this environmental disaster. It comprises ceramic plates, bowls, cups, and vases – or jars as he prefers to call them. They are made and painted by Wedd, the imagery that decorates them a profusion of the dying and dead sea-life he has observed, and more fantastic forms drawn from the worlds of pre-modern imagery and his own imagination.

Aside from one of Wedd’s jars, all his pieces here are blue-and-white ceramics – mid-fired clay body with a cobalt under-glazing, in which the distinctive blue brush-painting is made. Blue-and-white ceramics have a certain universality as a cultural form. Their origins lie in China and Iraq in the ninth century, and from the seventeenth century they have been traded, copied and adapted globally, from Chinese Jingdezhen, to Dutch Delftware, English tin-glazed ware and local variants in many other cultures. Wedd is drawn to it on precisely this account – it is a form that, due to its centuries-long history of global appropriation and reappropriation, belongs to nobody and everybody. In some of his pieces, Wedd’s sinuous and breezy brushwork decorates the exteriors and interiors of vessels with waves and swells, His brushwork here recalls that of Chinese and Japanese brush painting, and his waves are inflected with something of the ukiyo-e style. These are conscious references, and indeed quotations. In other imagery derived from old European sources, his brushwork just as readily takes on the intricate quality of the hatching and linework of European etching. In one such work, a hand-built shallow bowl shows a human skull as part of a still life of dead sea creatures: A stubby-nosed dolphin, squid, stingray, fishbones, and a wide-eyed pufferfish are mixed together with strands of sea grasses and weeds, like a grotesque bouillabaisse. Wedd’s brushwork, precise and delicate here, precisely delineates the dissolution of life on the shore amidst the bloom. It is a refence to the vanitas tradition, where a still life would contain a hidden symbolic reminder, a memento, of mortality and decay within their splendid displays. One could read Wedd’s Bloom as a whole as an example of contemporary vanitas: a commentary on dying seas, mass die-offs, and fragile ecosystems.

The imagery with which Wedd covers his pottery has an extraordinary cultural reach. Sometimes it is realistic, detailed and documentary, sometimes it is naïve and cartoon-like, sometimes it is spontaneous, with the ease and delicacy of a Japanese brush painting. Often it is wryly appropriative. Other bodies of work include fine-grained documents of vernacular cultures, including the intricate folklore of surfing, rendered with sharp humour and deep understanding. His visual language also spans art history and classical learning, the harvest of an autodidact who grew to intellectual maturity in the first flush of postmodernism. Here this imagery comes into its own, utilised to idiosyncratic, powerful, phantasmagoric effect. The vanitas is one example of this, and there are many more particular examples to discover here. There are mer-people shown dead, dying – and on a number of cups, vomiting. On the side of one cup a skeletal mer-person appears (with, yes, two ribcages – one for its human torso, and one for its fish body). On its other side is a Boschian figure, fish-headed with a skeletal human body – a reverse mer-person. There are many other vignettes of wit among the cups: including a coughing cockle, and a dead fish emitting bubbles spelling out SOS.

Attached to the exterior of one cup is a vertical brownish bubbling smear. It is rather like a bird shit, or a smudge of earth impregnated with poison algal matter. In fact, it is the remnant of a pyrometric cone, a small pyramidal clay artefact that deforms or bends at a specific temperature in the kiln, used by ceramicists to determine the kiln’s heat. By serendipitous happenstance, this one ended up stuck to the side of the cup during the process of firing.

Elsewhere, in the waves and eddies circling around the interiors of bowls and cups, there are references to the maelstrom, the infamous whirlpool off the Norwegian coast, made famous in Poe’s eponymous short story. Wedd points out in a YouTube video that one reason we know so much of Greek mythology is because of the illustrations on pots. He doesn’t mean that we learn the stories, as such, for these are given in the textual sources; rather we learn the appearances of the heroes, gods and monsters that populate these tales. On one cup, there is a diving harpy-like monster, grasping what appears to be a snake in its talons, its image perhaps drawn from the red-figure Ancient Greek stamnos in the British Museum showing Odysseus and the Sirens. Here it seems to allude to the vast feast of carrion served up to the birds that patrol the shoreline. While Classical Greek poetry and art was often dedicated to heroic acts worthy of commemoration, it is worth mentioning that Wedd’s pottery turns this imagery to record a relentless suffering in nature and gesture toward its likely human causes. Another striking image, decorating a plate, shows a dead shark washed ashore. Wedd has taken it from an old encyclopaedia which furnishes many of his more arcane images. The print Wedd draws on is itself adapted (in reversed form, as prints often are) from a late eighteenth century engraving of a great white shark by Marcus Bloch (fig. 1). Bloch was still influenced by the idea of sharks as ‘sea dogs’, as they were commonly known in Europe in earlier centuries, and the physiognomy of this shark’s head accordingly resembles that of a dog, while the tail is fixed in a Baroque flourish. In Wedd’s version, the shark retains Bloch’s weird physiognomy. Its grotesque features though are rather better suited to Wedd’s dead animal, its mouth opened in a rictus, expelling a poisoned froth.

These works of pottery, despite the imagery painted on them, are not memorials or didactic objects. They are domestic vessels and plates, and they are designed to be used. The handles of the cups, for instance, are crafted to be comfortably and firmly held, and the cups themselves are made to hold a drink. Wedd’s intention is clear. He asks us to consider this extraordinary environmental disaster while we undertake everyday activities in our intimate domestic spaces – and to reflect, perhaps with melancholy, horror or wry humour, on a distressing reality that is also, as I write, intimately close to hand.